|

There was an error in a press release communicated via email to announce Wild Tiger's latest scientific publication. Sarika Khanwilkar is not a National Geographic Explorer as stated in the press release. Sarika co-wrote and worked on a successful grant in 2019 along with 2 colleagues and, more recently co-wrote, along with 4 others, a successfully funded Meridien grant. These grants were submitted as apart of Project Dhvani work.

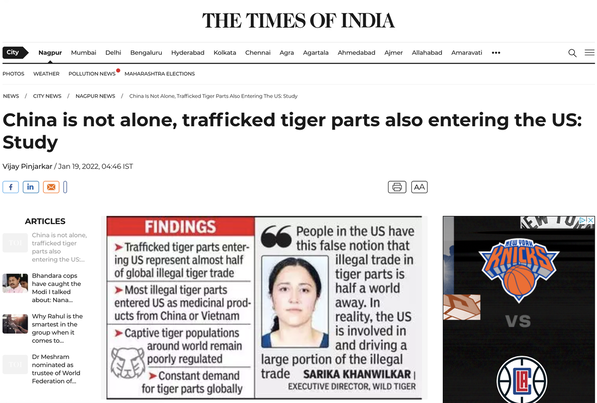

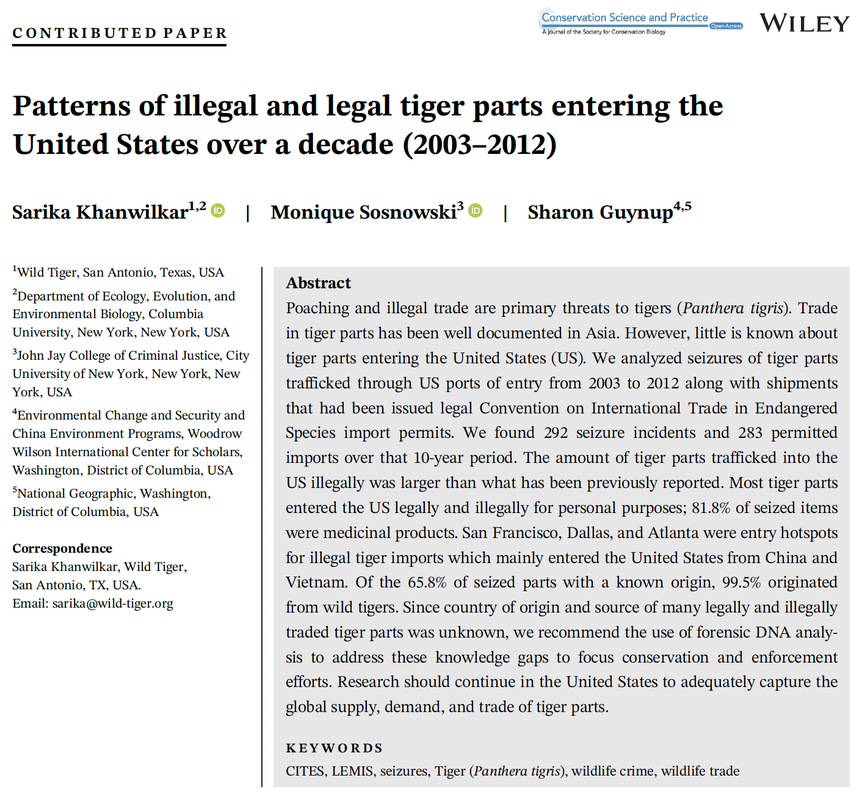

"People in the US have this false notion that the illegal trade in tiger parts is half a world away. In reality, we in the US are involved in and driving a large portion of the illegal trade. This research is a step to better understand the role of the US in the global tiger trade, which will improve policy and enforcement and direct future research efforts." - Sarika Khanwilkar While the US is a major supporter of tiger conservation efforts worldwide, its role in trafficking of illegal tiger parts is substantial. This is the conclusion of a recently published study Patterns of illegal and legal tiger parts entering the United States over a decade (2003 – 2012) published by Sarika Khanwilkar, Founder of Wild Tiger, National Geographic Explorer, PhD candidate at Columbia University, Monique Sosnowski, PhD candidate at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and Sharon Guynup, a journalist, National Geographic Explorer and Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

The study is in Conservation Science and Practice, which publishes solutions-oriented and science-based conservation research. Email [email protected] to get a PDF of the paper. More than 130 participants logged on to Zoom to watch Sarika present on "Tigers behind bars: captive tigers and the United States." It was an honor for Sarika to be an invited speaker of Symbiosis University's Biodiversity Cell and share some of Wild Tiger's work with people in India.

At the end of April, the pandemic became an emerging crisis across India. In central India, rural communities already experiencing health and socioeconomic disparities were hit hard by the economic repercussions of work restrictions to daily wage jobs that they depend on.

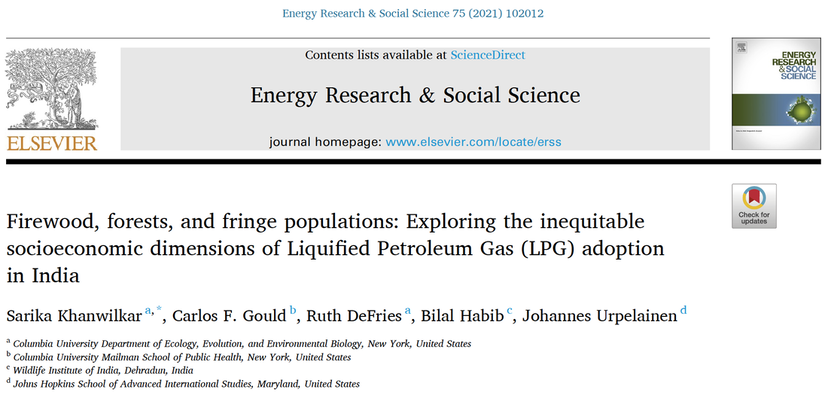

The Last Wilderness Foundation, an Indian-based Non-Governmental Organization, works with communities, who are largely Indigenous, around Panna, Bandhavgarh, and Kanha Tiger Reserves in central India. As the crisis in India expanded, they mobilized their team to provide essential items to communities such as food and face masks. We knew we had to help. In an impromptu fashion, Sarika asked her social media followers to donate to the cause. In less than a week, US donors gave over $3,000 to help support the Last Wilderness Foundation's (LWF) work to aid communities during the covid-19 crisis. On May 8th, Sarika and Bhavna Menon, a Program Manager at LWF, spoke on Instagram Live about the impact of those donations and why supporting communities and working with people is helping wildlife. Watch the conversation at this link. One of the most memorable parts of the conversation was when Bhavna said that people in these communities were not so scared of dying of the virus; they were scared of starvation. Please keep India in your heart and mind during this difficult time. Investing in and understanding communities that live in and around central India's forests are important for creating a future where people and wildlife can coexist. As apart of Sarika's PhD work, she published her first, first-author peer review paper entitled Firewood, forests, and fringe populations: Exploring the inequitable socioeconomic dimensions of Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG) adoption in India in the journal of Energy Research and Social Science.

Firewood is the primary cooking fuel for many households in central India. This can be problematic because of the household air pollution caused by burning firewood indoors and burdens women and children in particular, who are in charge of cooking and collecting firewood. Finally, firewood collection can be a dangerous task when entering forests with wild animals such as tigers or leopards, and impacts forest health. The government has provided LPG to poor households since 2016, through a program called Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yoyjana, which is meant to address some of the health impacts of using firewood for cooking. Sarika, along with her co-authors, used social survey data collected in 2018 from 4,994 households living within 500 villages living in forested regions of central India, along with a satellite-derived measure of forest availability to investigate cooking fuel use. They documented LPG adoption, the timing of this adoption, pre or post-2016, and patterns of firewood collection. The probability of cooking with LPG was lowest for marginalized social groups. Households recently adopting LPG, likely through the government scheme, were poorer, more socially marginalized, less educated, and have more forest available nearby than their early adopter counterparts. While 90% of LPG-using households continue to use firewood, households that have owned LPG for more years report spending less time collecting firewood, indicating a waning reliance on firewood over time. Policies targeting communities with marginalized social groups living near forest can further accelerate LPG adoption and displace firewood use. Despite overall growth in LPG use, disparities in access to clean cooking fuels remain between socioeconomic groups in India. Please email [email protected] to access a PDF version of the paper. Last December, we were hopeful that the Big Cat Public Safety Act (Big Cat Act) was close to becoming a federal law because it had passed the House. Unfortunately, the bill was not voted on by the Senate before the congressional session came to an end. Each congressional session lasts 2 years and once it ends, and if a bill hasn't been voted into law by that time, the process to become a law restarts.

The Big Cat Act (H.R. 263 of the 117th Congress) was introduced in the House in early January of 2021. This is the first step in adopting this important federal legislation. For years, the Big Cat Public Safety Act (Big Cat Act) waited for action in the US Congress while the number of captive tigers in the US continued to proliferate, their exact numbers and whereabouts unknown. The Big Cat Act is important because it would end the practice of cub petting and begin the process of overseeing captive tiger ownership and breeding. On December 3rd, the Big Cat Act (H.R. 1380 of the 116th Congress) passed the House, and we are now hoping that the Senate will vote on this issue before the end of the year.

Until Wild Tiger’s advocacy work on the Big Cat Act, people from places where tigers are wild were absent from discussions about the need to address the US tiger crisis. However, regulating captive tigers in an international issue. Wild tigers from Tiger Range Countries are threatened with poaching, done to supply parts to the illegal wildlife market. Poaching of wild tigers is stimulated by the demand market for tiger parts, that is sustained by parts from captive born tigers. Wild Tiger obtained almost 2,000 signatures of people from India in a letter to Congress which asked the US to adopt the Big Cat Act as a law. We presented the petition, Indians against illegitimate tiger breeding and ownership in the US, to members of Congress. If the Big Cat Act becomes a federal law, the US will be a leader in captive tiger regulation. Next, Tiger Range Countries will need to continue to apply pressure to other countries where captive tigers require further regulation. |

AuthorRegular updates from the Wild Tiger team. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed